|

|

Early Henry Clay Cameras may have been the only folding dry plate cameras to use a

sliding drop-bed design. The sliding drop-bed had a benefit of having the camera’s

entire weight centered over the tripod, which reduces the amount of stress on the

camera’s frame and body. This may have been a major design goal however it also

had several drawbacks.

The first has to do with securing The Henry Clay Camera to a tripod. The camera must first be opened and locked before being attached to a stand. Under normal conditions, a photographer would first mount a camera to the stand then open. Since the sliding bed must be opened before attaching to the stand, there is a greater risk of damaging the camera because the bed has a tendency to slide back and forth along the focusing rails. The next drawback has to do with the camera's rigidity. Once mounted on a tripod or stand, the camera does not have a solid feel. This is because a small amount ‘play’ must be allowed between the brass plate lip and the focusing rail groove in order to allow the bed to slide freely.

As far as it can be ascertained, the change to a hinged-bed locking strut design may have been primarily for rigidity. In his review that appeared in the Scovill & Adams 1893 American Annual Of Photography, W. Jerome Harrison commented on the redesigned Henry Clay Camera’s feel:

The first has to do with securing The Henry Clay Camera to a tripod. The camera must first be opened and locked before being attached to a stand. Under normal conditions, a photographer would first mount a camera to the stand then open. Since the sliding bed must be opened before attaching to the stand, there is a greater risk of damaging the camera because the bed has a tendency to slide back and forth along the focusing rails. The next drawback has to do with the camera's rigidity. Once mounted on a tripod or stand, the camera does not have a solid feel. This is because a small amount ‘play’ must be allowed between the brass plate lip and the focusing rail groove in order to allow the bed to slide freely.

As far as it can be ascertained, the change to a hinged-bed locking strut design may have been primarily for rigidity. In his review that appeared in the Scovill & Adams 1893 American Annual Of Photography, W. Jerome Harrison commented on the redesigned Henry Clay Camera’s feel:

The appearance of a hinged bed model in the 1893 Annual implies that it could have been available as early as mid-1892 because Scovill & Adams

Annuals were normally published in December of the prior year.

The 1891 Henry Clay Camera

Assessment of the Sliding Bed Design

Assessment of the Sliding Bed Design

Construction and operation of a sliding-bed design Henry Clay Camera is

significantly different from a strut-bed version. In contrast to beds that

are attached to the main body using a piano style hinge, a sliding-bed is

attached to the camera’s parallel focusing rails using a pair of mahogany

blocks. Each block is solidly secured to the bed with a pair of large wood

screws.

On top of each block is an oversized brass plate, which is slightly wider than the wood block. The brass plate is positioned flush with three sides of the block, while the overhanging fourth side (facing the parallel focusing rails) forms a small overhang or lip.

The brass lip nests inside grooves running the length of geared brass focusing tracks attached to the outside of the focusing rails. This arrangement allows the bed to slide along the focusing rails. The geared focusing track also serves to guide the front standard as it is racked forward.

Depressing a brass stud on the front panel releases a catch allowing it to slide downward. Once the panel clears the body, it can be rotated 90 degrees to act as a bed for the front standard.

On top of each block is an oversized brass plate, which is slightly wider than the wood block. The brass plate is positioned flush with three sides of the block, while the overhanging fourth side (facing the parallel focusing rails) forms a small overhang or lip.

The brass lip nests inside grooves running the length of geared brass focusing tracks attached to the outside of the focusing rails. This arrangement allows the bed to slide along the focusing rails. The geared focusing track also serves to guide the front standard as it is racked forward.

Depressing a brass stud on the front panel releases a catch allowing it to slide downward. Once the panel clears the body, it can be rotated 90 degrees to act as a bed for the front standard.

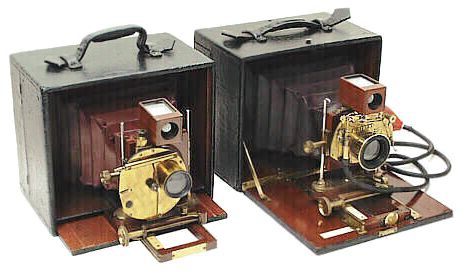

Comparison of the 1891 sliding bed

and c.1893 hinged bed body patterns.

and c.1893 hinged bed body patterns.

Multi-Lens Cameras | View Cameras | Self-Casing Cameras | Solid Body Cameras | References & Advertisements

Home | What's New | Show Schedule | Wanted | For Sale | Links | Site Map | Email

Home | What's New | Show Schedule | Wanted | For Sale | Links | Site Map | Email

Copyright ©1999 by Rob Niederman - ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

See also:

• The Henry Clay Camera

• The Henry Clay Stereoscopic Camera

• The Henry Clay Regular Camera

• Henry Clay 2d Camera

Return to the Self-Casing Cameras page

• The Henry Clay Camera

• The Henry Clay Stereoscopic Camera

• The Henry Clay Regular Camera

• Henry Clay 2d Camera

Return to the Self-Casing Cameras page

"The camera front possesses very remarkable powers of adaptation. It can be raised or

depressed over a space of above two inches; it swings both ways from its centre (thus

giving vertical lines on the ground-glass, although the tripod may have either tilted or

depressed); it has a lateral motion of 2½ inches, and it can even be bent round until it

looks like the Irishman's gun, which was made to "shoot round the corner." In any of

these positions it can be instantly and firmly clamped by a brass lever, and indeed the

strength and rigidity of the whole instrument is remarkable."

The bed is then slid rearward into a recessed cavity located under the

body. The final step secures the focusing rail using a large rotating brass

lock located in front of the rail hinge. The front standard can now be

racked forward readying the camera for hand or stand use.